2012-05-18: Déjà-vu …

” In the early hours of the morning of Saturday, 14th February 1981, a disastrous fire swept through a building called the Stardust in the North Dublin suburb of Artane during the course of a St. Valentine’s Night ‘disco’ dance. Forty eight people were killed and one hundred and twenty eight seriously injured. The overwhelming majority of the victims were young people. “

‘Introduction’, Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry on the Fire at the Stardust, Artane, Dublin, on the 14th February 1981. Report dated 30 June 1982.

As a young architect in private practice … I witnessed, at first hand, the Dublin Fire ‘Establishment’ disappear from public view, without trace, after the Stardust Fire Tragedy. It was almost impossible, for at least a year afterwards, to have a meeting with any Fire Prevention Officer in the Dublin Fire Authority. This was a very valuable lesson.

Later, following the publication of the Stardust Tribunal Report … were its Recommendations implemented … with urgency … and conscientiously ? No way. For example, it was more than ten years after the Stardust Fire before an inadequate system of legal National Building Regulations was introduced in Ireland. And to this day, the system of AHJ monitoring of construction quality, throughout the country, is weak and ineffective … lacking both competent personnel and resources !

The proof of the pudding is in the eating … and one of the results, also in Dublin, has been last year’s debacle at the Priory Hall Apartment Complex … where all of the residents had to leave their expensive apartments for fire safety (and many other) reasons. The tip of a very large iceberg. See my post, dated 18 October 2011 .

And this is where the problems usually begin …

” There has been a tendency among students of architecture and engineering to regard fire safety as simply a question of knowing what is required in terms of compliance with the regulations. The recommendation of the Tribunal of Enquiry into the Summerland Disaster that those responsible for the design of buildings should treat fire safety as an integral part of the design concept itself, has not yet been reflected in the approach to the subject at university level. There is still clearly a need for a new approach to the structuring of such courses which will in time bring to an end the attitude of mind, too prevalent at the moment, that compliance with fire safety requirements is something that can be dealt with outside the context of the overall design of the building. “

‘Chapter 9 – Conclusions & Recommendations’, Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry on the Fire at the Stardust, Artane, Dublin, on the 14th February 1981. Report dated 30 June 1982.

This Recommendation has still not been implemented … and note the reference to the earlier fire at the Summerland Leisure Centre in 1973, on the Isle of Man, when 50 people were killed and 80 seriously injured.

Today … the same attitude of mind, described so well above, stubbornly persists in all sectors, and in all disciplines, of the International Construction Industry … even within ISO Technical Committee 92: ‘Fire Safety’ !

.

Which brings me, neatly, to the recent question posed by Mr. Glenn Horton on the Society of Fire Protection Engineers (SFPE-USA) Page of LinkedIn ( http://www.linkedin.com/groups?gid=96627 ). As usual, the shortest questions can prove to be the most difficult to answer …

” Can you expand on, or point to where anyone has discussed, the ‘very flawed design approach’ please ? “

.

ESSENTIAL PRELIMINARIES …

1. Foundation Documents

I am assuming that ‘people-who-need-to know’, at international level, are familiar with the Recommendations contained in these 2 Reports …

- NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). September 2005. Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster: Final Report on the Collapse of the World Trade Center Towers. NIST NCSTAR 1 Gaithersburg, MD, USA ;

and

- NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). August 2008. Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster: Final Report on the Collapse of World Trade Center Building 7. NIST NCSTAR 1A Gaithersburg, MD, USA ;

… and the contents of the CIB W14 Research WG IV Reflection Document … which, together with its 2 Appendices, can be downloaded from this webpage … https://www.cjwalsh.ie/progressive-collapse-fire/ … under the section headed: ‘April 2012’.

However … I am utterly dismayed by the number of ‘people-who-need-to know’ … who do not know … and have never even bothered to dip into the 2 NIST Reports … or the many long-term Post 9-11 Health Studies on Survivors which have already revealed much priceless ‘real’ information about the short and medium term adverse impacts on human health caused by fire !

CIB W14 Research Working Group IV would again strongly caution that Fire-Induced Progressive Damage and Disproportionate Damage are fundamental concepts to be applied in the structural design of all building types.

.

2. Technical Terminology

While attending the ISO TC92 Meetings in Thessaloniki, during the last week of April 2012, I noticed not just one reference to ‘fire doors’ in a Draft ISO Fire Standard … but many. It surprised me, since I thought this issue had been successfully resolved, at ISO level, many years ago. There is no such thing as a ‘fire door’ … and the careless referencing of such an object, which has no meaning, in building codes and standards has caused countless problems on real construction sites during the last 20-30 years.

Please follow this line of thought …

Fire Resistance: The inherent capability of a building assembly, or an element of construction, to resist the passage of heat, smoke and flame for a specified time during a fire.

Doorset: A building component consisting of a fixed part (the door frame), one or more movable parts (the door leaves), and their hardware, the function of which is to allow, or to prevent, access and egress.

[Commentary: A doorset may also include a door saddle / sill / threshold.]

Fire Resisting Doorset / Shutter Assembly: A doorset / shutter assembly, properly installed or mounted on site, the function of which is to resist the passage of heat, smoke and flame for a specified time during a fire.

… and so we arrive at the correct term … Fire Resisting Doorset … which, as an added bonus, also alerts building designers, construction organizations, and even AHJ inspectors, to the fact that there is more involved here than merely a door leaf.

Now then, I wonder … how, in any sane and rational world, can the term Fire Resistance be used in relation to structural performance during a fire, and the cooling-phase afterwards ? Yet, this is exactly what I read in the building codes of many different jurisdictions. Do people understand what is actually going on ? Or, is the language of Conventional Fire Engineering so illogical and opaque that it is nearly impossible to understand ?

And … if this problem exists within the International Fire Science & Engineering Community … how is it possible to communicate effectively with other design disciplines at any stage during real construction projects. The artificial environments found in academia are not my immediate concern.

.

3. Fire Research & Development outside CIB W14 & ISO TC92

In 2012 … there is something very wrong when you have to struggle to persuade a group of people who are developing an ISO Standard on Design Fire Scenarios … that they must consider Environmental Impact as one of the major consequences of a fire to be minimized … along with ‘property losses’ and ‘occupant impact’. This is no longer an option.

Environmental Impact: Any effect caused by a given activity on the environment, including human health, safety and welfare, flora, fauna, soil, air, water, and especially representative samples of natural ecosystems, climate, landscape and historical monuments or other physical structures, or the interactions among these factors; it also includes effects on accessibility, cultural heritage or socio-economic conditions resulting from alterations to those factors.

So … how timely, and relevant to practitioners, are ISO Fire Standards ? Perhaps … obsolete at publication … and not very ??

And … there is lot more to the Built Environment than buildings …

Built Environment: Anywhere there is, or has been, a man-made or wrought (worked) intervention in the natural environment, e.g. cities, towns, villages, rural settlements, service utilities, transport systems, roads, bridges, tunnels, and cultivated lands, lakes, rivers, coasts, and seas, etc … including the virtual environment.

.

We should be very conscious that valuable fire-related research takes place outside, and unrelated to, the established fire engineering groupings of CIB W14 & ISO TC92. But I am curious as to why this research is not properly acknowledged by, or encouraged and fostered within, the ‘system’ ?

Example A: Responding to Recommendation 18 in the 2005 NIST WTC Report … a Multi-Disciplinary Design Team published an article in the magazine Bâtiment et Sécurité (October 2005) on The PolyCentric Tower. I very much enjoy giving practitioners a small flavour of this work, whenever I make presentations at conferences and workshops …

.

Example B: In spite of a less than helpful submission (to put it mildly) from ISO TC92 Sub-Committee 4 … ISO 21542: ‘Building Construction – Accessibility & Usability of the Built Environment’ was finally published in December 2011 … but it was developed by a Sub-Committee of ISO TC59: ‘Buildings & Civil Engineering Works’ …

.

With the involvement and support of ISO Technical Committee 178: ‘Lifts, Elevators & Moving Walks’ during its long gestation … ISO 21542 is now able to indicate that all lifts/elevators in a building should be capable of being used for evacuation in the event of a fire. This is already a design feature in a small number of completed Tall Building Projects. Once more, this is no longer an option.

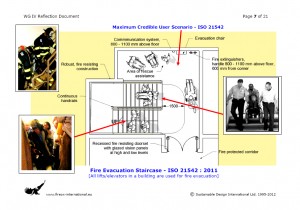

In addition … if a Fire Evacuation Staircase has a minimum unobstructed width of 1.5 m (from edge of handrail on one side of the staircase to edge of handrail on the opposite side) … this will be sufficient to facilitate the following tasks …

- Assisted Evacuation by others, or Rescue by Firefighters, for those building users who cannot independently evacuate the building, e.g. people with activity limitations … shown above, on the right, is assistance being given by three people (one at each side, with one behind) to a person occupying a manual wheelchair ;

- Contraflow Circulation … emergency access by firefighters entering a building and moving towards a fire, while people are still evacuating from the building to a ‘place of safety’ remote from the building … shown above, bottom left, is how not to design an evacuation staircase (!) ;

- Stretcher Lifting … lifting a mobility-impaired person, who may be conscious or unconscious, on a stretcher ;

- Firefighter Removal & Contraflow … shown above, top left, is removal of a firefighter from a building by colleagues in the event of injury, impairment, or a fire event induced health condition … while other firefighters may still be moving towards the fire.

Note that in a Fire Evacuation Staircase … all Handrails are continuous … each Stair Riser is a consistent 150 mm high … each Stair Tread/Going is a consistent 300 mm deep … and there are No Projecting Stair Nosings.

Most importantly … in order to assign sufficient building user space in the design of an Area of Rescue Assistance … ISO 21542 also provides the following Key Performance Indicator … just one aspect of a ‘maximum credible user scenario’ …

10% of people using a building (including visitors) have an impairment, which may be visual or hearing, mental, cognitive or psychological, or may be related to physical function, with some impairments not being identifiable.

Is There Any Connection Between Examples A & B ? There is, and it is a connection which is critical for public safety. The following Performance Indicator illustrates the point …

Innovative Structural Design – Perimeter Core Location – Design for Fire Evacuation – Evacuation for All

” A Building must not only remain Structurally Stable during a fire event, it must remain Serviceable for a period of time which facilitates:

- Rescue by Firefighters of people with activity limitations waiting in areas of rescue assistance ;

- Movement of the firefighters and those people with activity limitations, via safe and accessible routes, to Places of Safety remote from the building ;

- With an assurance of Health, Safety & Welfare during the course of this process of Assisted Evacuation. “

[Refer also to the Basic Requirements for Construction Works in Annex I of the European Union’s Construction Product Regulation 305/2011 – included as Appendix II of the CIB W14 WG IV Reflection Document. Are the Basic Requirements being interpreted properly … or even adequately ??]

.

ANSWERS TO THE QUESTION …

The Greek Paper is included as Appendix I of CIB W14 WG IV Reflection Document … in order to show that Fire-Induced Progressive Damage is also an issue in buildings with a reinforced concrete frame structure. It is more straightforward, here, to concentrate on buildings with a steel frame structure.

a) Use of ‘Fire Resistance'(?) Tables for Structural Elements

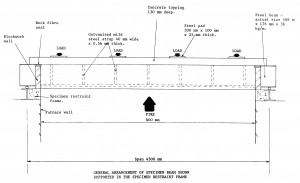

We should all be familiar with these sorts of Tables. The information they contain is generated from this type of standard test configuration in a fire test laboratory …

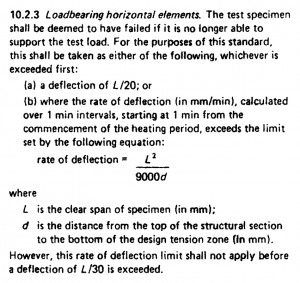

… and this sort of criterion for ‘loadbearing horizontal elements’ in a fire test standard …

A single isolated loaded steel beam, simply supported, is being tested. As deflection is the only type of deformation being observed and measured … the critical temperature of the steel, i.e. the point when material strength begins to fail rapidly and the rate of beam deflection increases dramatically … is the sole focus for all stakeholders.

Using these Tables, it is very difficult to escape the conclusion that we are merely interior decorators … applying flimsy thermal insulation products to some steel structural elements (not all !) … according to an old, too narrowly focused, almost static (‘cold form’) recipe, which has little to do with how today’s real buildings react to real fires !

This ‘non-design’ approach is entirely inadequate.

.

With regard to the use of these Tables in Ireland’s Building Regulations (Technical Guidance Document B), I recently submitted the comments below to the relevant Irish AHJ. These same comments could just as easily apply to the use of similar Tables in the Building Regulations for England & Wales (Approved Document B) …

” You should be aware that Table A1 and Table A2 are only appropriate for use by designers in the case of single, isolated steel structural elements.

In steel structural frame systems, no consideration is given in the Tables to adequate fire protection of connections … or limiting the thermal expansion (and other types of deformation) in fire of steel structural elements … in order to reduce the adverse effects of one element’s behaviour on the rest of the frame and/or adjoining non-loadbearing fire resisting elements of construction.

In the case of steel structural frame systems, therefore, the minimum fire protection to be afforded to ALL steel structural elements, including connections, should be 2 Hours. Connections should also be designed and constructed to be sufficiently robust during the course of a fire incident. This one small revision will contribute greatly towards preventing Fire-Induced Progressive Damage in buildings … a related, but different, structural concept to Disproportionate Damage …

Disproportionate Damage

The failure of a building’s structural system (i) remote from the scene of an isolated overloading action; and (ii) to an extent which is not in reasonable proportion to that action.

Fire-Induced Progressive Damage

The sequential growth and intensification of structural deformation and displacement, beyond fire engineering design parameters, and the eventual failure of elements of construction in a building – during a fire and the ‘cooling phase’ afterwards – which, if unchecked, will result in disproportionate damage, and may lead to total building collapse. “

Coming from this background and heritage … it is very difficult to communicate with mainstream, ambient structural engineers who are speaking the language of structural reliability, limit state design and serviceability limit states.

.

b) NIST Report: ‘Best Practice Guidelines for Structural Fire Resistance Design of Concrete and Steel Buildings’ (NISTIR 7563 – February 2009)

At the end of Page 18 in NISTIR 7563 …

” 2.7.2 Multi-Storey Frame Buildings

In recent years, the fire performance of large-frame structures has been shown in some instances to be better than the fire resistance of the individual structural elements (Moore and Lennon 1997). These observations have been supported by extensive computer analyses, including Franssen, Schleich, and Cajot (1995) who showed that, when axial restraint from thermal expansion of the members is included in the analysis of a frame building, the behaviour is different from that of the column and beam analyzed separately.

A large series of full-scale fire tests was carried out between 1994 and 1996 in the Cardington Laboratory of the Building Research Establishment in England. A full-size eight-storey steel building was constructed with composite reinforced concrete slabs on exposed metal decking, supported on steel beams with no applied fire protection other than a suspended ceiling in some tests. The steel columns were fire-protected. A number of fire tests were carried out on parts of one floor of the building, resulting in steel beam temperatures up to 1000 °C, leading to deflections up to 600 mm but no collapse and generally no integrity failures (Martin and Moore 1997). “

Those were Experimental Fire Tests at Cardington, not Real Fires … on ‘Engineered’ Test Constructions, not Real Buildings !! And … incredibly, for a 2009 document … there is no mention at all of World Trade Center Buildings 1, 2 or 7 !?! Where did they disappear to, I wonder ? Too hot to handle ???

Computer Model Verification and Validation (V&V) are very problematic issues within the International Fire Science and Engineering Community. The expected outcome of a Model V&V Process, however, is a quantified level of agreement between experimental data (and, if available, real data) and model prediction … as well as the predictive accuracy of the model.

Now … please meditate carefully on the following …

” NCSTAR 1A (2008) Recommendation D [See also NCSTAR 1 (2005) Recommendation 5)

NIST recommends that the technical basis for the century-old standard for fire resistance testing of components, assemblies and systems be improved through a national effort. Necessary guidance also should be developed for extrapolating the results of tested assemblies to prototypical building systems. A key step in fulfilling this Recommendation is to establish a capability for studying and testing components, assemblies, and systems under realistic fire and load conditions.

Of particular concern is that the Standard Fire Resistance Test does not adequately capture important thermally-induced interactions between structural sub-systems, elements, and connections that are critical to structural integrity. System-level interactions, especially due to thermal expansion, are not considered in the standard test method since columns, girders, and floor sub-assemblies are tested separately. Also, the performance of connections under both gravity and thermal effects is not considered. The United States currently does not have the capability for studying and testing these important fire-induced phenomena critical to structural safety.

Relevance to WTC 7: The floor systems failed in WTC 7 at shorter fire exposure times than the specified fire rating (two hours) and at lower temperatures because thermal effects within the structural system, especially thermal expansion, were not considered in setting the endpoint criteria when using the ASTM E 110 or equivalent testing standard. The structural breakdowns that led to the initiating event, and the eventual collapse of WTC 7, occurred at temperatures that were hundreds of degrees below the criteria that determine structural fire resistance ratings. “

The design approach outlined in NISTIR 7563 is not only very flawed … it lacks any validity … because very relevant and important real fire data has been totally ignored. The Cardington Experimental Fires were not all that they seemed.

.

c) Current ISO TC92 International Case Study Comparison

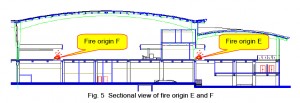

Structural Fire Engineering Design of an Airport Terminal Building serving the Capital City of a large country (which shall remain nameless) … constructed using Portal Steel Frames …

My first concern is that the Structural Fire Engineering Design has been undertaken in isolation from other aspects of the Building’s Fire Engineering Design.

On Page 3 of the Case Study Report …

” 4.2 Objectives & Functional Requirements for Fire Safety of Structures

The fire safety objectives of the airport terminal emphasize the safety of life, conservation of property, continuity of operations and protection of the environment. “

Should these not be the Project-Specific Fire Engineering Design Objectives ? Since when, for example, is ‘continuity of operations’ a concern in building codes ??

On Page 7 of the Case Study Report …

” 5.3 Identify Objectives, Functional Requirements & Performance Criteria for Fire Safety of Structure

The Fire Safety Objective of the Steel Structure: There should be no serious damage to the structure or successive collapse in case of fire.

The Functional Requirements are defined as the followings:

(1) Prevent or limit the structural failure in case of fire so as to prevent the fire from spreading within the compartment or to the adjacent fire compartment or the adjacent buildings (to prevent fire spread) ;

(2) Prevent or limit the partial structural failure in case of fire so as to protect the life safety of the occupants and firefighters (to protect life safety) ;

(3) Prevent or limit the structural deformation or collapse so as not to increase the cost or difficulties of the after-fire restoration (to reduce reconstruction cost).

One of the following Performance Requirements shall be met:

(1) The load-bearing capacity of the structure (Rd) shall not be less than the combined effect (Sm) within the required time, that is Rd ≥ Sm. (The maximum permitted deflection for the steel beam shall not be larger than L/400, and the maximum stress of the structure under fire conditions shall not be larger than fyT) ; or

(2) The fire resistance rating of the steel structure (td) shall not be less than the required fire resistance rating (tm), that is, td ≥ tm ; or

(3) Td – the critical internal temperature of the steel structure at its ultimate state shall not be less than Tm (the maximum temperature of the structure within required fire resistance time duration), that is Td ≥ Tm. (300 ℃) “

Once again … we see an emphasis on critical temperature, beam deflection (only), and material strength. L/400 is an impressive Fire Serviceability Limit State … a different world from L/20 or L/30 … but what about other important types of steel structural member deformation, e.g. thermal expansion and distortion ??

Furthermore … if there is a major fire in the area under the lower roof (see Section above) … because of structural continuity, any serious impact on the small frame will also have an impact on the large frame. For Structural Fire Engineering reasons … would it not be wiser to break the structural continuity … and have the small and large portal frames act independently ?

It is proposed that the Portal Frames will NOT be fully fire protected … just the columns, up to a height of 8 metres only. If ‘conservation of property’ and ‘continuity of operations’ are important fire engineering design objectives in this project … why isn’t all of the steel being fully protected ??? What would be the additional cost, as a percentage of the total project cost ?

What exactly is infallible about current Design Fires and Design Fire Scenarios ??? Not much. And in the case of this particular building, should a ‘maximum credible fire scenario’ be at least considered ?

And … what is the fire protection material, product or system being used to protect the Portal Frames ? Will it be applied, fixed or installed correctly ? What is its durability ? Will it be able to resist mechanical damage during the construction process … and afterwards, during the fire event ? What is the reliability of this form of fire protection measure ??

So many questions …

.

.

END